Engineered Desire, Designed Absence

Why the Netflix-Warner merger scares any non-white creator.

More than a century ago, Sigmund Freud made a destabilizing claim: human beings are not governed primarily by reason, but by desire. We are moved by urges we don’t fully understand, by wants that arrive before language. Freud called this realm the unconscious. He identified the force beneath the sentence. What he did not do was prescribe how institutions might use it.

That work was taken up by his nephew, Edward Bernays, often called the father of modern advertising. Edward recognized that if desire operates below consciousness, it can be guided. Not forced. Not coerced. Directed. Bernays understood something deceptively simple: people don’t buy products because they need them; they buy products because those products have been attached to feelings they already trust - freedom, power, belonging.

He put that insight to work with ruthless efficiency. He persuaded women to smoke by framing cigarettes as symbols of liberation - “Torches of Freedom,” he called them. He helped sell wars as moral necessities. He understood that you don’t sell cars; you sell sexual power. You don’t sell consumption; you sell identity.

Bernays called this the “engineering of consent.” What he was really engineering was attention: what gets seen, what gets repeated, what accrues value.

Crucially, Bernays believed desire was dangerous. Left unmanaged, it could destabilize systems. So desire had to be channeled, not freed - given safe outlets, familiar heroes, clean narrative arcs. Stories that soothe rather than disrupt. Stories that keep the machinery running.

This is where absence stops being accidental.

Fast-forward to the present. Marc Randolph, Bernays’ great-nephew, co-founded Netflix, a platform that does not simply distribute stories but actively trains audiences how to want them. Netflix does not shout. It nudges. Autoplay removes friction. Thumbnails are endlessly A/B tested. Algorithms learn what keeps viewers still. This is not propaganda in the 20th-century sense; it is something more intimate. Netflix does not tell us what to think. It shapes the conditions under which thinking happens.

This is no longer just the engineering of consent. It is the engineering of content.

When Netflix announced its acquisition of Warner Bros (still in limbo), the news was framed as a business milestone - scale, synergy, efficiency. But for many non-white creators, the moment landed differently. Media consolidation has always narrowed the range of stories that survive. Fewer gatekeepers rarely means more risk-taking. It usually means the opposite.

The question is not whether diverse stories can succeed. The data are clear. The question is whether they will be allowed to.

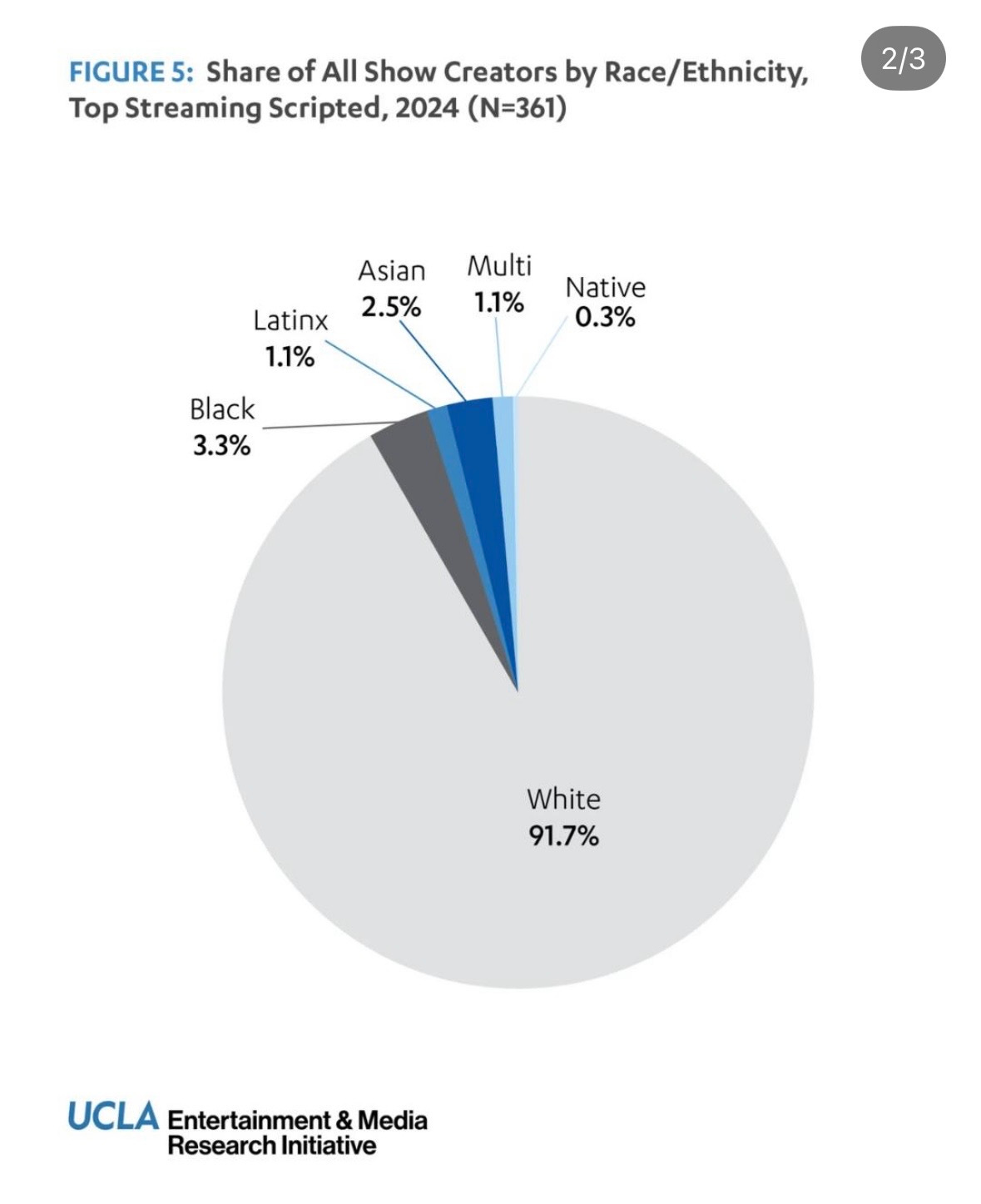

According to UCLA’s Hollywood Diversity Report 2025, Black, Indigenous, and people of color made up 44.3 percent of the U.S. population in 2024, yet accounted for just 25.2 percent of lead roles in top theatrical films, 20.2 percent of directors, and only 12.5 percent of writers.

Latinx representation was particularly stark: only 1 percent of lead roles in top films went to Latinx actors, despite Latinos being the largest and fastest-growing audience in the country. Latinos hold over $4 trillion in spending power. TRILLION. Let that sit… We subscribe. We show up. We have always shown up. And yet our stories, when they exist, are under-marketed, under-resourced, treated like experiments instead of investments.

This is not because diverse films fail. In fact, the report shows the opposite. Films with casts that were 41–50 percent BIPOC posted the highest median global box office in 2024, more than $230 million, dramatically outperforming films with the least diverse casts. BIPOC audiences also bought the majority of opening-weekend tickets for seven of the top ten films and twelve of the top twenty films at the global box office that year.

In other words, the myth that “diversity doesn’t sell” is not just outdated, it is empirically false.

And yet, in 2024, Hollywood moved backwards (once again) - films with the least diverse casts more than doubled compared to the previous year, while the share of films with highly diverse casts declined. Representation fell even as audiences continued to show up. This is where consolidation becomes dangerous.

When power concentrates, so does risk aversion. Algorithms trained on past success begin to mistake familiarity for universality. Stories that already sit at the center are reinforced; stories at the margins are labeled “niche.” Marketing budgets follow the same logic. Big money goes to projects presumed to appeal to “everyone,” while films and series led by creators of color are often released quietly, with minimal promotion and marketing budget - then cited as evidence that demand was never there.

This is how designed absence works.

Stories do more than entertain. They train desire. They teach audiences whose interior lives are worth lingering in, who is allowed complexity without punishment, who gets to fail and still be loved. When certain stories are consistently underfunded, under-marketed, or omitted altogether, the lesson is not subtle. Absence becomes instruction.

If desire can be taught, and Bernays proved that it could, then the absence of certain stories teaches people where to look and where not to. It teaches proximity instead of presence. It teaches creators to pre-edit their own imaginations before anyone else has to.

I felt this long before I had language for it: the quiet sense that something had been swapped out. The hero on screen was suave, but never muy suave. Polished, but drained of risk. Familiar enough to admire, distant enough to never challenge the story about who belongs at the center. Of course James Bond was white and British, not Brown and Dominican (Porfirio Rubirosa, google it).

What links Freud, Bernays, and the modern media landscape is not trivia about family lineage. It is an inheritance of ideas about power. Freud named desire. Bernays learned how to manage it. Algorithms now perform that management at global scale. The same psychological tools - emotional targeting, behavioral data, predictive modeling - used to sell products and political messages are now used to decide which stories are surfaced and which are buried.

This is not a conspiracy. It is a system built on incentives. Platforms reward what keeps attention. Attention rewards what feels familiar. Familiarity rewards what has already been centered. The loop reinforces itself, especially when fewer companies control more of the cultural supply chain.

That is why the Netflix–Warner merger matters. Not because it guarantees exclusion, but because it amplifies the conditions that have always produced it. Fewer decision-makers. Bigger bets. Narrower definitions of “safe.” And less room for stories that carry too much history, too much feeling, too much truth to be easily managed.

Liberation has never started with policy alone. It has always begun with sensation, with the body saying no before the mouth finds the words, with the realization that the world as presented is not the only one possible.

If desire can be taught, then liberation must be re-learned. That re-learning will not begin in a boardroom, a pitch deck, or a diversity statement. It begins in feeling. In remembering. In refusing to accept absence as natural.

It begins when we insist on telling the stories anyway, not because they are safe, but because they are true.

If you find medicine here, buy me a coffee and/or support me for just $3.75!

& buy a copy of Brown Enough (one for you, one for the homie, one for the neighborhood library) and listen to Season 3 of the podcast!

My man!!!